The crisp feeling in the air, the rustle of dry leaves skittering along the sidewalk, the scent of fresh apples — these things signal the most poetic time of the year, for me.

Others may wax nostalgic about spring or soft summer nights, and those things have their appeal. But nothing quite compares to the bittersweet bliss of October, when the world tilts toward the darkness again, at least in this hemisphere. There is a rush of energy to this autumnal shift, a sense of urgency. Time’s a wastin’, get the harvest in. The season hums with a “back-to-school,” anything-can-happen mood of fresh opportunity.

This mood changed my life back in October of 1969, when there were a lot of fresh ideas, and some recycled ones, adrift on the shared consciousness of our nation. At that time I had already dropped out of high school, dropped out of college, and tuned in to the mesmerizing pull of a group of scruffy musicians in the D.C. area who were gaining momentum on the local scene.

They started out as a trio, guitar, bass and drums. Within a few months that core had expanded to a collective whose appearances included anywhere from six to 12 performers on stage. The repertoire was eclectic and the group dynamic was volatile, but when they were going good, they were as good as anybody, and better than many.

For the last century, to play in a band has become almost a rite of passage for a large percentage of America’s youth. The type of music doesn’t matter. It’s the playing that defines us.

The United States is a nation of bands. But what makes a band different from individual musicians who may be more skilled and talented than the average band, is that bands can only exist through consensus. And consensus is never easy. Ask anyone in Washington, D.C.

In the beginning of the band that dominated my life for three years, we all lived together in one house. When the band grew too big to fit into the house we shared in D.C., we found an old farmhouse in the Virginia countryside and moved there. The house was big and rambling, but it wasn’t designed to accommodate a horde. There were enough rooms that could be used as bedrooms, but they weren’t equal in size or charm. The question of who should get the best, or biggest, room was discussed. In the end, it was decided that the order of choice would be decided by a cut of the cards. The day before the move happened to be the drummer’s birthday. He was late to the card cutting and as it turned out the card he drew was the lowest.

Yet, as the guys went through the house for the first time the next day (none of them had seen it before; in order to rent the house we had sent our most respectable looking pair to negotiate the deal, keeping the musicians out of sight) each found a room that suited his needs. And most were happy, with the possible exception of the organ player who chose one of the smallest rooms because it had the only private bath, which later proved to be nonfunctioning. Also one of the lead singers chose an attic room that had great potential after he lobbied to have the group pay for his building supplies to fix it up. Those supplies are probably still sitting up there in the dust.

But the drummer, choosing last, selected an overlooked room above the kitchen. It had its own private staircase to the kitchen, thus ensuring a good spot in the line for dinner, and was the warmest room in the house, a key plus in the drafty old structure.

We were happy for a while in that old house. Everything the band earned was used to pay our expenses. The musicians got one dollar per gig.

If that sounds like communism, I suppose it was to an extent. But it was more than that. It was a democratic commune. We debated every expenditure. The milk vs beer argument was never won by either side. And there were other, ahem, expenses.

By the time the band broke up a couple of years later, we were no longer living together. We got together for gigs, but the day-in-day-out sharing of good times and bad had lessened, and without that daily closeness, understanding and sympathy lose the race with self-interest and ambition.

Yet the funny thing is, the band enjoyed its peak when everyone was more concerned about the group as a whole than about themselves as individuals. The willingness to work for the good of the whole benefits all the parts.

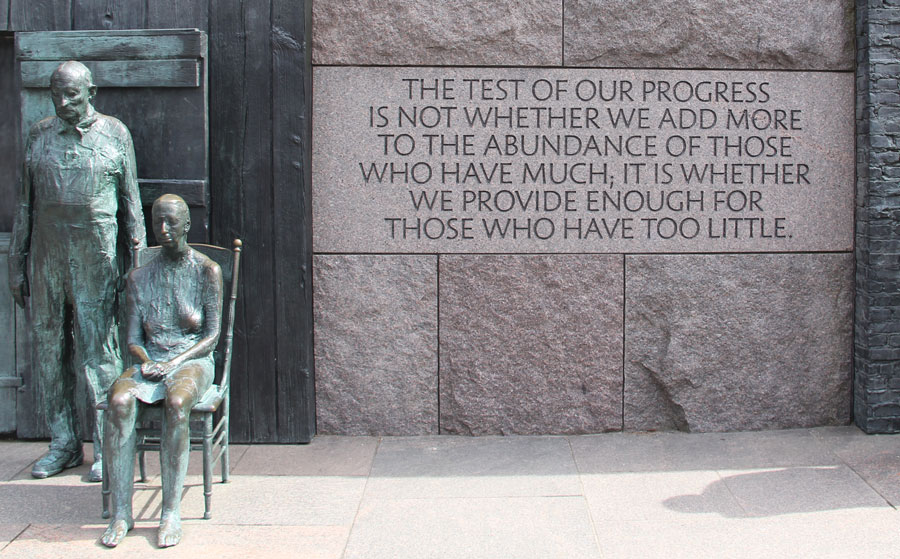

This is the key not simply to rock and roll survival, but to national strength. We in this country like to think of ourselves as champions of individual freedoms. But what made this country great in the first place was the readiness of all the individuals who sacrificed for the good of the whole.

It might sound corny, but sometimes nothing swings like the basics. The country that plays together stays together. We may never agree on the milk vs beer question, but as long as we keep the discussion civil, we still have a chance for greatness.