Now that I’m closer to being 70 than I am to the ‘70s, I find my enthusiasm for the hectic skirmish of modern life is tempered by the cold shower of perspective.

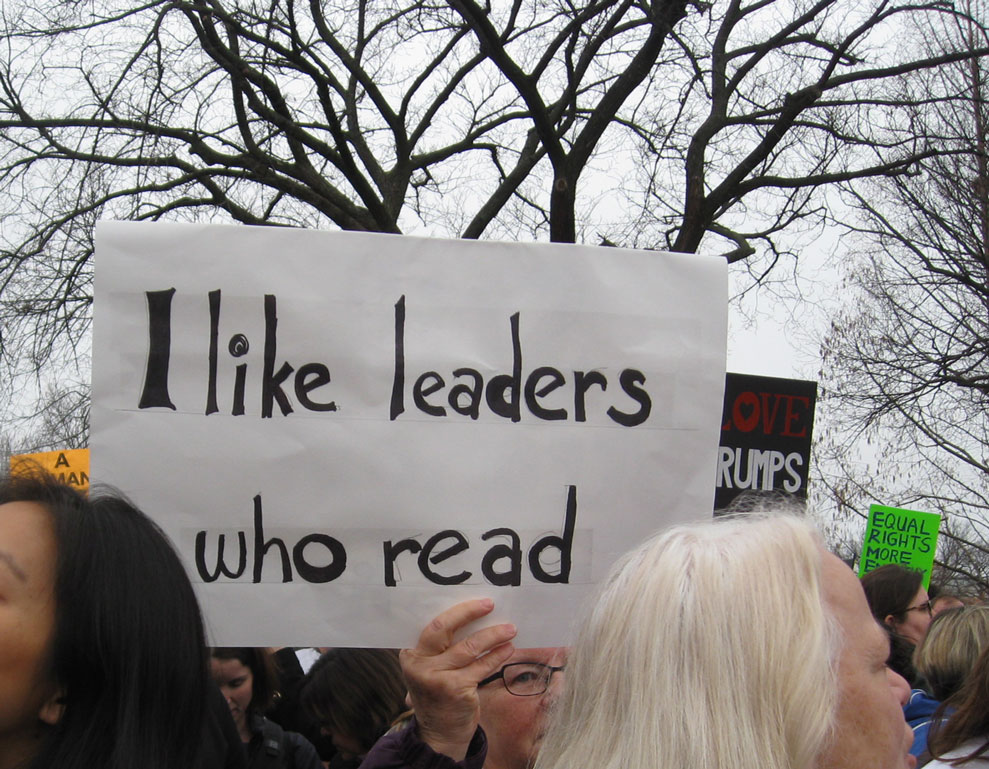

In January, as I joined thousands of women thronging the streets outside the Capitol rallying for justice and civil rights for all citizens of this still young country, I couldn’t help noticing how many of my fellow marchers were too young to have experienced the protests of the ‘60s and ‘70s. It was encouraging to see their passion and conviction that right must prevail over might. However, having witnessed more than a few wrong turns in the journey of this rough and tumble democracy, I’ve come to feel that flashy speeches and flag waving are just smoke and mirrors. The nitty gritty work of democracy is accomplished in the quiet dedication of scholars and the unflinching courage of soldiers.

Real heroes have no need for boasting and threats. They simply do their jobs.

Lately I’ve been thinking about the scholars and soldiers who helped establish this democracy of ours. We hear the stories of George Washington and the lore of Jefferson in school. But how many of us have the time and energy to dig deeper into the complexities of the characters who shaped our national heritage?

I am no scholar. I’m more of a cultural mayfly, skimming the surface of the mysteries of life. Recently I read with delight “And the Pursuit of Happiness,” Maira Kalman’s illustrated journal, published in 2008, a moment of historic optimism. Her piquant drawings and dry observations offer a refreshing mix of offbeat humor and admiration for our history and democracy itself.

She covers so much territory, from Leif Ericson to Herman Melville, from Dolley Madison to Ruth Bader Ginsberg. And in each case, Kalman delivers surprising insights into the past and what we can learn from it.

I was particularly intrigued by the chapter on Thomas Jefferson. Having spent most of my life in Virginia, I thought I knew all there was to know about our third president, the one who wrote, “I cannot live without books.” He also wrote the Declaration of Independence. He was 33 when he wrote it. He owned hundreds of slaves, even though he was against slavery. As Kalman puts it, “The monumental man had monumental flaws.”

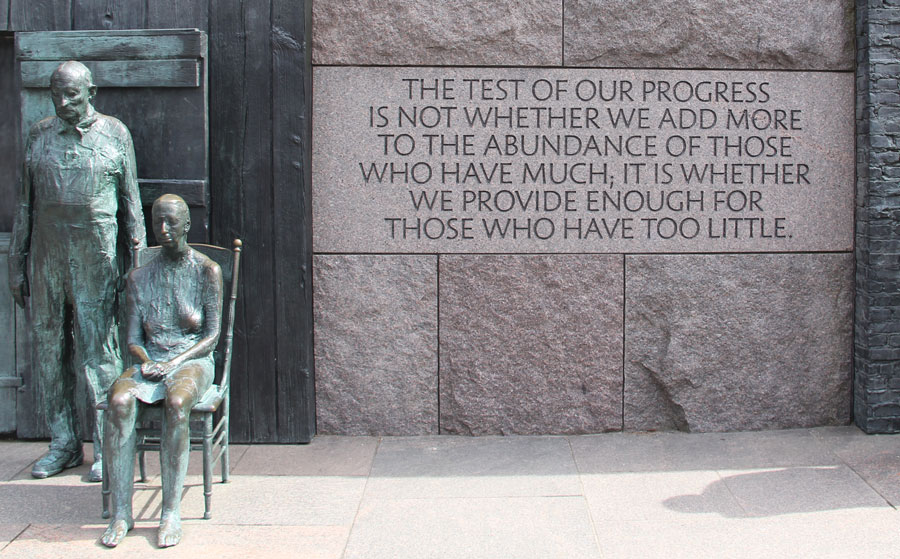

It’s hard to imagine any of the current crop of “so-called” statesmen measuring up to the achievements of the early men and women who dedicated their lives to the ideals of this democracy. But in addition to the sketches of famous patriots, Kalman also offers vignettes of lesser known men and women working then and now to keep the democratic dream alive.

I was heartened to learn of the Thomas Jefferson quote engraved above the door to the women’s room in the Capitol Building. “Enlighten the people generally and tyranny and oppressions of body and mind will vanish like evil spirits at the dawn of day.”

Read on!