Logic never made much sense to me.

When I took it in college I was confounded by its rules and axioms. The so-called self-evident principals never resonated with me in the way that poetic flights of sheer fantasy always have.

In general, I’m a pretty gullible person. Just ask my brothers, or the guy who scammed $12 off me back in 1978 to pay for his bus fare to see his dying grandmother. Yeah right.

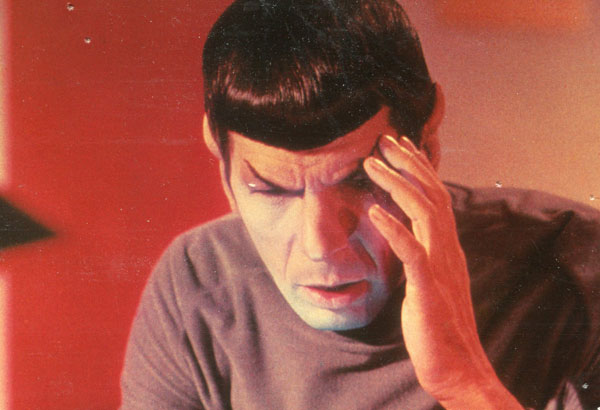

But arguments based on pure logic always woke the mule in me. Until a certain Starfleet Science Officer known as much for his pointy ears and greenish skin as for his brilliant analytical mind came into my life.

I never saw the original Star Trek during its three season journey through the wasteland of prime time television from 1966 to 1969. I was exploring other worlds myself back then. But in the summer of 1971 my brother Billy introduced me to the series, which was in heavy reruns and already gaining altitude in the pantheon of science fiction legends.

The great thing about reruns is that they allow a newbie to catch up fast. With Billy’s coaching I was soon fully engaged, a shy but enthusiastic Trekkie. I never went to a convention. Although I did stand in line to sit in the original Captain’s chair when the 20th anniversary Star Trek exhibition opened at the Smithsonian.

So, is Spock really dead? I mean, I know Leonard Nimoy died yesterday, and I’m saddened by this, although grateful that he had such an amazing life and eventually came to terms with his Spock legacy.

For me, Spock was always the one. I loved all the originals: Kirk with his over-the-top thespian shtick, McCoy with his irritable grit, Scottie with his mechanical wizardry and never-say-die pluck, Uhura with her poise and courage, and the playful Sulu and Chekhov.

But it was Spock whose gravity, credibility, and wry humor made me believe that sometimes a little logic can be magical.

Leonard Nimoy himself, according to reports and things he wrote in his 1975 memoir, “I Am Not Spock,” and later in the 1995 memoir, “I Am Spock,” came to realize that, illogical as it may be, the character of Leonard Nimoy had so much to do with the character of Spock, that the two “melded” in the minds of adoring fans.

As a lifelong romantic fool myself, I found the character of Spock the most compelling precisely because he always tried to resist irrational behavior, yet, because he was half-human, he was vulnerable like all the rest of us.

The truth is, humans aren’t rational. Yet we continue, some of us anyway, trying to make sense of this life, trying to assign reasons for the infinite mysteries that surround us. It’s kind of sweet. And that’s why, if I had to choose one Star Trek character to be my desert island companion, it would be Spock, the tall cool one. I’d mind-meld with him any day.

Go in peace Leonard Nimoy Spock. And thanks for all the fascinating years.