Since I moved back to the D.C. area last year I’ve been listening to a lot of bluegrass music on the radio. There was a time when I would change the station at the first clang of a banjo. But you know how it is. Time changes everything, and as my need for high energy rock and roll has waned, my appreciation for mandolins, fiddles and even banjos has grown.

Music enthusiasts often joke about the differences between various genres of popular music, noting how country songs tend to be about trucks, drinking and broken hearts, whereas bluegrass music often focuses on trains, home, and the difficulties of finding and keeping true love. I don’t have much to add to the musical conversation when the subject is trucks, or drinking, or matters of the heart. But when it comes to trains, I can blow my own horn.

Trains ran through my childhood. I didn’t care about them particularly at the time. It didn’t matter. My father’s love of trains began when he was a boy and lasted until his dying breath.

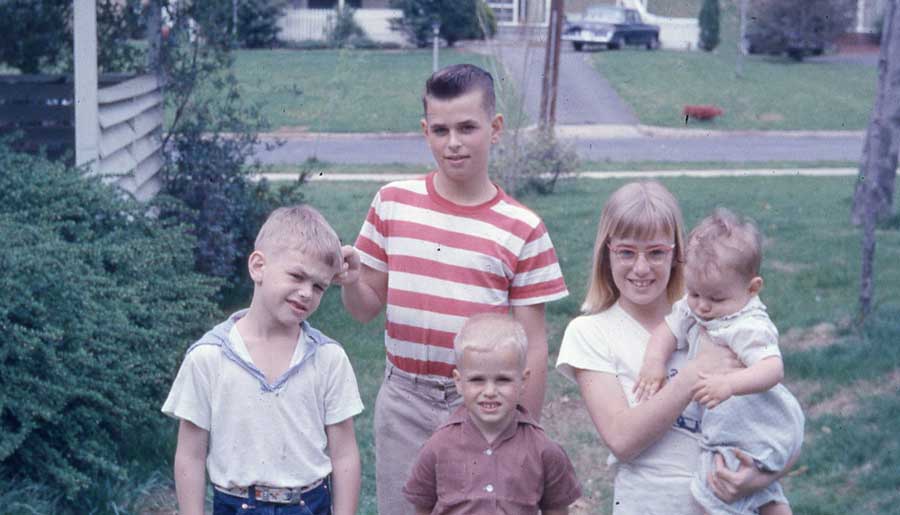

I didn’t get it when I was growing up. I mean, when I was a little kid I thought it was kind of cool the way my dad built model trains, and the way he would always take us to see trains, and stop the car on road trips to watch them go by, take pictures, and count the cars, listen to the horns. Some of my earliest memories of my dad are of him, head down, concentrating on some engine he was building at his small desk in my parents’ bedroom. With five kids in a tiny three bedroom house—no basement, family room or rec room—my dad had to put his dreams of a train layout on hold in the early days of his career.

But once we moved to a bigger house with a basement, he poured a lot of his time and money into building an impressive collection of replica HO gauge trains. By the time he had seven children he had more trains than he knew what to do with, and not much energy or time to spend with them, but he continued to hope that one of us kids would catch the fever and take over the layout.

That never happened. One by one each of us would try to take an interest in Dad’s hobby. But trains simply didn’t mean anything to us. They were Dad’s thing.

He would try to make us catch his enthusiasm. He had recordings of trains that he would play on the stereo, so loud that it sounded like the train was pulling into the living room. And he would be grinning like a little kid, sure that if we could only see what he saw in his head, hear what he heard in his memories, we would want to share it.

We all tried. But there was no way we could experience the romantic era of war-time train travel that meant so much to our dad.

But here’s the thing: all of these bluegrass laments about lost love and homesick sorrow go on and on about the lonesome whistle’s blow and the general sadness of trains leaving, etc.

My dad was never happier than when he was on a train. He lit up whenever he heard one in the distance. He looked forward to seeing them, riding on them, learning about them.

I’m glad my father got so much joy from his fascination with trains. I’m grateful that he shared his enthusiasm with me and my brothers. I’ve always loved the sound of trains in the distance, perhaps as a result of my father, or perhaps just because, let’s face it, the sound of a train passing in the distance is a kind of poetry. If you listen the right way.

Since he died last fall I hear music every time a train sounds in the night.

And sometimes, it’s a bluegrass song.