I once went to a truly scary movie by accident. It was “Repulsion,” a riveting psychological suspense thriller starring Catherine Deneuve as a delusional young woman alone in her apartment, imagining the worst. There was very little actual blood, no monsters lurching, biting or slashing. The horror was all in the heroine’s mind, and Ms. Deneuve conveyed her terror with such conviction that I could hardly bear to sit through the entire thing.

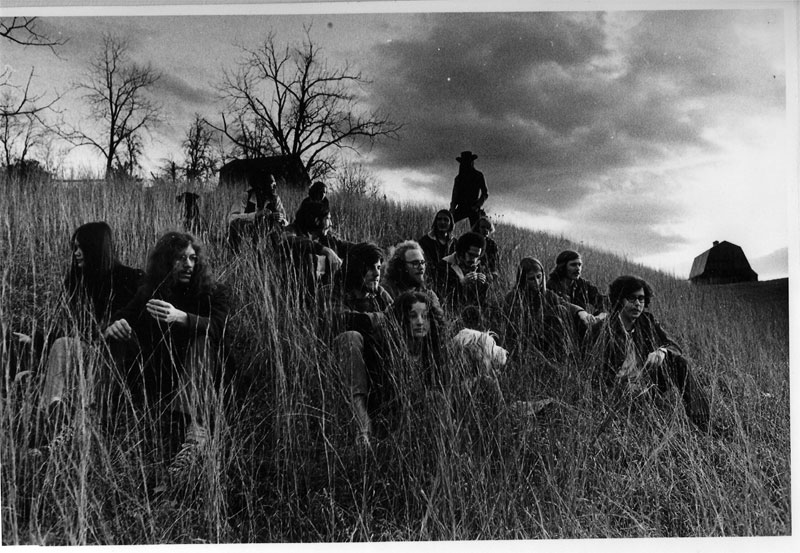

So. Not such a big fan of the horror genre. That said, I appreciate a finely wrought suspense film or novel, and admire the mastery of Hitchcock, the snarky brilliance of Polanski. But I wonder sometimes about the current gentrification of horror. Tonight is Halloween, a holiday which once occupied a single day, and was celebrated mostly by children under the age of twelve. Now in this country, the only country where Halloween has undergone a kind of Hollywood makeover, the Halloween season lasts for the entire month of October, and adults throw themselves into it with far greater abandon than the kids. I know, because I was once one of the happy party people arrayed in wigs and sparkles and fake gore, where applicable, and it was fabulous fun.

But as I wandered past the Halloween stores in the malls near Washington, DC, last week, I found myself wondering if perhaps we haven’t taken the thing too far, and if so, why?

For myself I know that Halloween used to offer a kind of release, a temporary escape from the altogether more frightening and far more entrenched terrors of the modern world. I’d list them but I don’t see any point in Pox News. Maybe the reason Halloween has grown so huge commercially is that people are responding to the underlying paranoia that lurks like a poisonous gas beneath the surface of our slick technological confidence.

If only werewolves and vampires and zombies were all that we had to fear.

I just finished reading “Boneshaker,” a cool steampunk novel by Seattle author Cherie Priest which explores the ways in which we humans allow fears and rumors to keep us from taking positive steps to fix problems. I related to the novel not only because it was set in a kind of alternate Seattle, but because the heroine is a mother battling hordes of undead and fiendish psychopaths in addition to her own sense of inadequacy as she tries to make things right with her only son. I like a heroine who can kick ass when it’s called for, while still retaining a core of emotional vulnerability.

That’s just one reason I detest most of the “women-in-jeopardy” films and novels which purport to be entertainment. Women all over the world are in enough jeopardy, and have been since the days when they were considered chattel. To perpetuate barbaric attitudes and to depict them in such quantities that people get numb to the ideas embedded in them seems criminal to me.

However, if the annual crop of slasher films is any indication, clearly the hooligans are dictating the playbook these days. It seems a large number of people enjoy screaming in horror at the movies.

I guess I understand. In the face of of global warming, nuclear threats, terrorists and plagues, it’s easier to avert an imaginary disaster than to work to prevent the real thing. I could just scream.