I had reservations about going to see the “Pulse” exhibit at the Hirshhorn. When I heard that visitors were expected to allow their fingerprints to be scanned in and projected large for all the world to see, I felt that modern knee-jerk cringe. Aren’t we all supposed to be concerned about our privacy, especially in view of the massive data breaches that have come to light?

I wasn’t always so uptight. But paranoia grows like mildew, out of sight until it’s everywhere.

Yet from the moment I stepped into the curving darkened gallery where Mexican artist Rafael-Lozano Hemmer’s works are on display, I was mesmerized by the drama and energy in the room. Lights were flashing on the ceiling. Images were constantly scrolling on the wall. Voices filled with hushed delight bubbled in the air.

I stuck my index finger in the first print reader without a qualm, and was immediately shocked to hear my own heart, pounding loud and clear. At the same time, an image of my fingerprint, taller than I am, appeared on the wall, taking its place in the interactive fingerprint stream moving implacably along the wall. Instagrammers huddled in the shadows trying to take it all in.

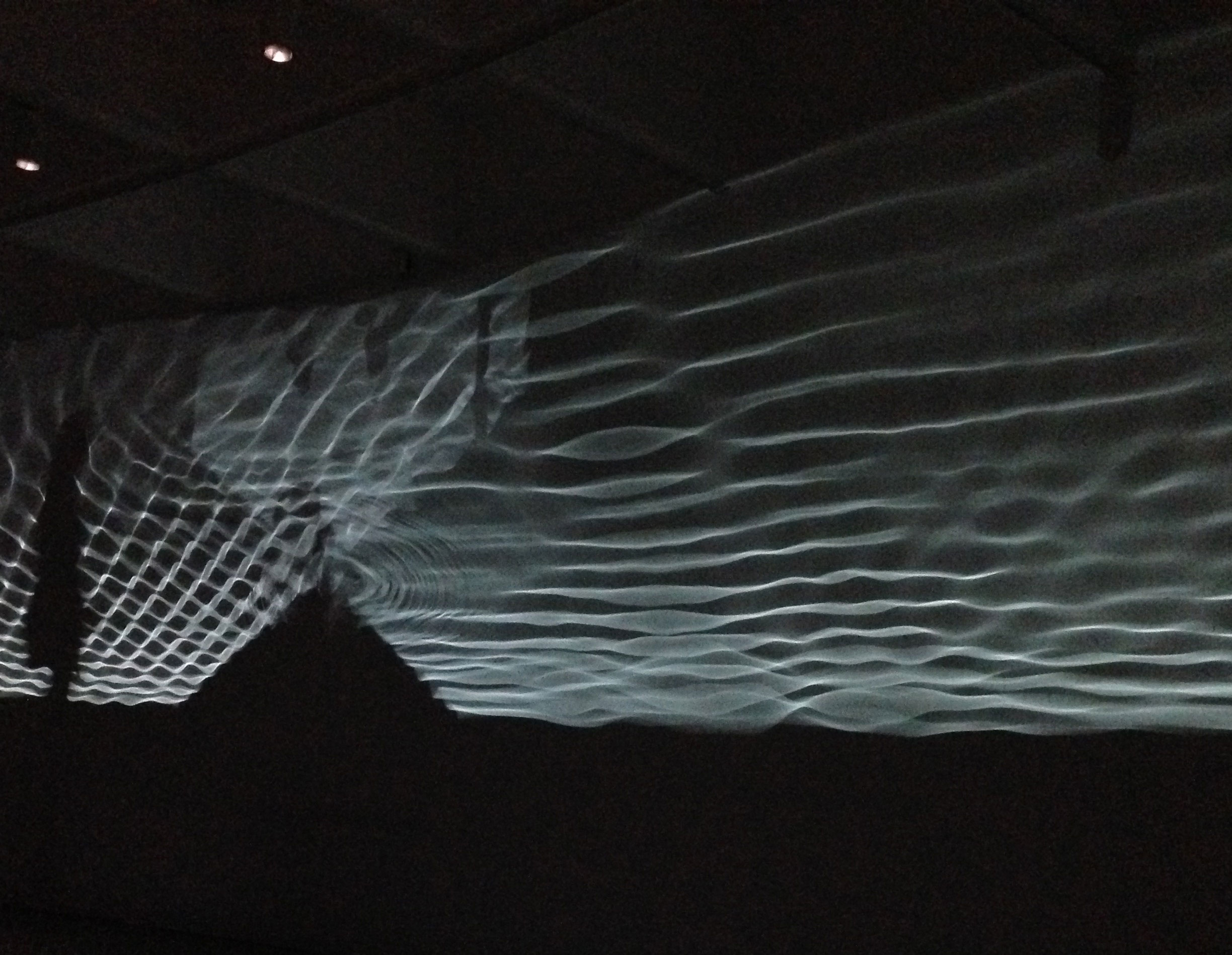

We are all programmed at a very young age to recognize visual art. We’re taught to look for it on walls, static and quiet. But it’s rare to find art that makes the invisible visible. At the Pulse “Tank,” a shallow pool on the floor in the center of the exhibit, visitors may place a hand on a sensor, which transmits their pulse to the pool, causing ripples of light to be projected onto the wall. When two people on opposite sides of the pool project their pulses at the same time, a rhythmic pattern dances on the wall.

This shared rhythm is at the heart of the exhibit. The pulse which beats below the surface of all life is out of sight most of the time, and too quiet to hear beneath the cacophony of modern human “civilization.” In Hemmer’s “Pulse Room” you can grip a pair of sensors to light one of the many ceiling bulbs which flash on and off, beating audibly in time with your heart. Your own little heartbeat’s star turn only lasts a minute or so, until the next person in line steps up and lends a beat. But your light doesn’t disappear right away. It moves down the line, joining the hundreds of other lights beating in the darkness, until it’s time for you to go.

Sort of like life right? We are all here such a short time, part of the ever-shifting cosmic drum circle.

The truth is, I am you and you are me and we are all replaceable and irreplaceable. Life is not about grabbing and holding and hording. It’s about passing on. It’s about waving into the universe.

Hello Universe. Earth sends its love.