When your birthday falls on or around Christmas, people tend to offer you sympathy, as if it must be your loss, being overshadowed, and most likely overlooked, by the grander celebrations taking place worldwide.

I was never bothered. For me, the lights, the music, the cookies, the hint of magic in the frosty air, all lent a festive note to the annual observation of my entry into this particular life, which has outlasted my childish dream of happy endings for us all. I now know far too much to put my weight on that flimsy branch. At this point in the narrative I am high up on the tree, and avoid looking down whenever possible.

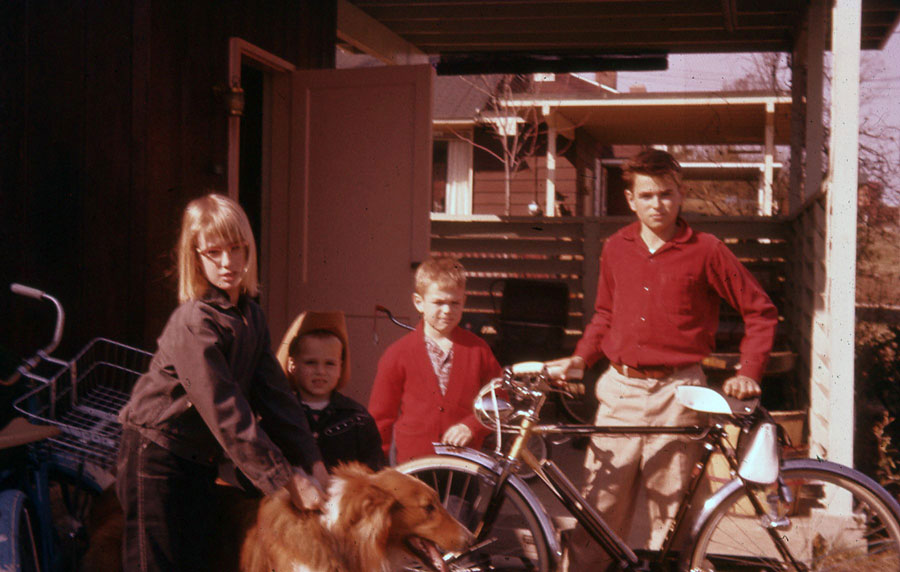

However, during that brief golden age when I still tried to twist the facts as they entered my precocious mind, wanting to believe in such a character as Santa Claus, for instance, while preferring not to believe that my parents were liars, I had a few Christmases that imprinted on my emotional retina as firmly as any snowy Currier and Ives print.

Christmas only happened in one place back then: my grandparents house in Erie, Pennsylvania. Even after my father moved our family down to Virginia, we still drove over the river and through the Pennsylvania Turnpike tunnels to the deep snow and cousin-rich comfort of Erie, a town whose hey-day was over long before I was born there. I didn’t know this then, and wouldn’t have cared. It was the one place where I felt safe from the mockery of my peers.

One of the most disorienting things about moving to Virginia was the not-so subtle shift in what qualified as humor among the children my age. Whether it was my sheltered nerdiness that drew their attention, or simply their instinct to rough up newcomers, whatever. I was shy to begin with; after a few months of southern “hospitality” I was disinclined to open up to anyone. It took me years to learn the system, and to develop my own protective shell of tough humor.

In our current climate of paranoia and aggression, a sense of safety seems more elusive than ever. I feel for parents who send their kids to public school, and I have nothing but the highest respect for the teachers brave enough to keep trying to bring light into this modern dark age.

It’s tempting to draw the wagons and lock down in full defensive mode. But if we give up on all the things that make life worth living, then the lunatics have won.

Humor is an essential part of humanity. When people lose the ability to laugh, especially at themselves, they risk losing their ability to empathize, and without empathy there can be no compassion. And without compassion … Right.

So here we are. Another Christmas season. Songs of joy and peace, etc. And, as usual, the world seems poised on the brink of another apocalyptic finale. Well, if we’ve learned anything from Hollywood it’s that nothing is ever final. There’s always a sequel, a prequel or a remake. In real life we’re fascinated by makeovers. We’re told there are no do overs.

But who really knows? Maybe life is like those trick candles on the birthday cake that keep relighting themselves. Maybe we get to keep blowing our chances until we get it right, like in Kate Atkinson’s weirdly compelling novel Life After Life.

Seems like a lot of work, if you ask me. But you didn’t. So I’ll just get back to blowing out these candles. Time’s a wastin’.