The following is an excerpt from a work in progress, “Not From Around Here.”

For a shy child, one problem with reading books to escape the difficulties of live human interaction is that if you’re always reading, you’ll never make eye contact with another human. Tunneling into books to escape being alone becomes a kind of self-defeating tactic. You read because you’re alone, and you’re alone because you read.

After sizing up the available companions in my school and new neighborhood, I swiftly came to the conclusion that the only people I could trust not to ridicule or attack me were my family. I read constantly. And when I got my first library card I was elated to have access to a quiet place where I could get as many books as I wanted for free.

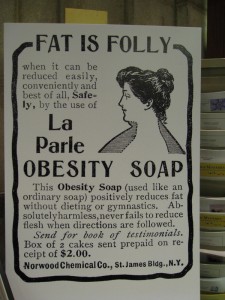

All of this reading took its toll on my eyes, I guess, because by the time I was eight I had to get glasses, another nail in the coffin of my socialization. This was long before glasses became the trendy fashion accessory worn by hollow-cheeked models in ads from Dolce & Gabbana and Prada. This was back when young women were trained to accept the axiom “men don’t make passes at girls who wear glasses,” as if that were a bad thing. Since I had no interest in any of the boys my age, I didn’t care. My first pair of glasses was made of red plastic with a brick pattern. I thought they were cool. Which just shows how truly far out of touch with reality I was as an eight-year-old.

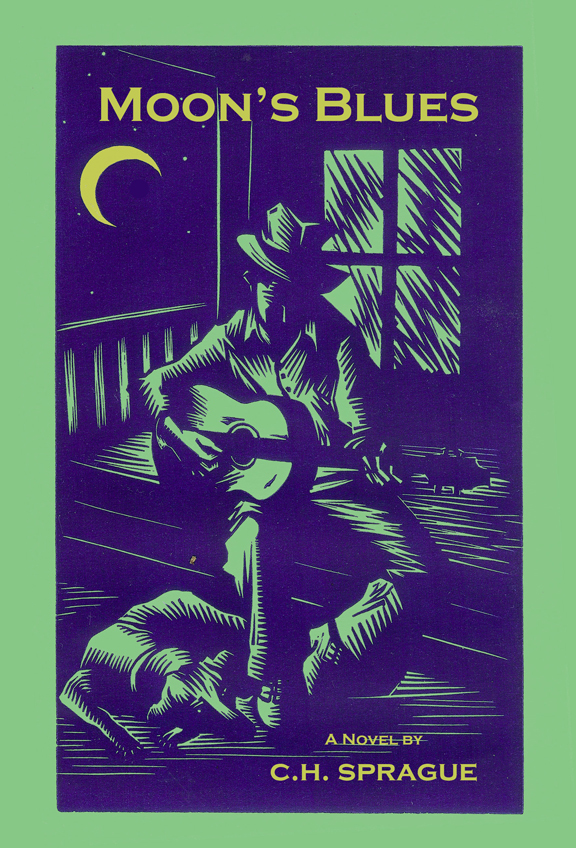

However, I went even further after I discovered the literary love of my life on the shelves of the public library. I don’t remember which book it was. At that point in his long career he’d already written probably sixty. But I do know that the first time I encountered the sentences, the vocabulary, the tone, and the timing of P.G. Wodehouse I wanted to live in his world. Of course, it was an imaginary world, an England which had ceased to exist even before the Second World War. But I didn’t know that, nor, I suspect, would I have cared. In Wodehouse’s carefree world no one dies, no one really suffers, and it only rains if it helps the plot along. And the plots are a confection of confusion, quirky characters and adroit literary style that simply made all my childhood angst vanish like an 18th century silver cow creamer. You had to be there.

Naturally, it wasn’t long before I began to act out my allegiance to this rarified literary world. I began to use phrases like “right ho” and “surely not” and to call people in my family “Old Bean.” I affected an English accent and imagined that it convinced strangers that I truly was not from around there.

My mother must have seen all of this as a cry for help. She kept pushing me to go and make friends with this or that neighborhood child. On the occasions when she would force me out the door and I had to try to play whatever mindless game was the order of the moment – kick the can or hide and seek – I would sneak back at the earliest opportunity and sequester myself in my room with a good book.

I had accepted the idea that I would never have friends, when suddenly, later that same year, I had two. The first was a boy five years older than I and confined to a wheelchair by muscular dystrophy. Tex had two younger brothers, who became friends with two of my brothers, and I was introduced to Tex, who pretty much lived in one room in his house. He was smart and lonely, and when he asked if I wanted to play a card game we began a friendship that lasted for the next two years until he died on Christmas Day. Tex taught me to play chess, and we worked our way through the entire book of Hoyle, as well as playing all varieties of board games. I had never considered the possibility of him dying, and neither his family nor mine ever took me aside and mentioned that it might happen. When it did I was stunned, and completely non-plussed by the “celebration” of his life which took place afterward. All my plans to grow up and find a cure for muscular dystrophy so Tex and I could live happily ever after were shattered.

But my grief was alleviated by the newfound wonder of the girl next door. I never would have met her if my mother hadn’t pushed me outside and told me to go over and knock on the door. It took me hours to work up the courage. This girl was pretty, blonde, blue-eyed and well dressed. I wore hand-me-downs from my older brother, or clothes my mother picked out for me. My hair was not something I understood how to “do” and I had no concept of chitchat.

Yet, in spite of all this, miraculously, Cyndie seemed to want to be friends. Only in retrospect can I see how as an only child of a mother who moved around a lot and was working on her second, or maybe it was third, husband, Cyndie may have had to learn how to make friends fast out of necessity. At any rate, I was elated that she accepted me, Old Beans and all.

Little did I know that my friendship with the sweet, wholesome-looking girl next door would crack open the door to a life of bohemian pretensions and kickstart the motorcycle of rebellion that roared into full-throated life in the mid-sixties.

We called him Uncle Rick. After all, he wasn’t Cyndie’s father. He wasn’t the type. In spite of being married to Cyndie’s mother, he still had the fresh scent of a boyfriend hardly broken in. He was dapper but casual, sort of like Cary Grant on a tropical vacation. He drank, smoked, and told risqué jokes that made my mother laugh. My father took an instant dislike to him. Naturally, I worshipped him. Cyndie and I sang songs for him, planned parties for our parents in an unsuccessful attempt to bring them together, and generally hung out together, even though she was a year ahead of me in school. The year we were together in a mixed class, with fifth and sixth graders studying in the same room, was the highlight of my elementary career. At the end of the year we performed in the school talent show doing an apache dance to the theme from “Peter Gunn.” I played the part of the man, with my longish hair under a hat. At the end of the dance, which was choreographed in classic fifties TV-style by Cyndie’s mom, I took off my hat and let my hair down. The audience ate it up. It was my first, and only, stage success until years later in high school when I made a brief splash in the Junior Jollies as Cher, singing “I Got You Babe” with Mike Willis, who later went on to become a respected professional actor, as Sonny.

But getting back to Uncle Rick. I should have seen the end coming. But of course, in my childish way, I imagined we would live next door to each other forever. Instead, six months after Tex died, Cyndie went off on a trip around the world with her mother and Uncle Rick. She sent me postcards, a present from the Philippines, and eventually a letter from Hawaii explaining how her mother was divorcing Rick, who was on his way to Tahiti alone. Tahiti. Cyndie stayed on in Hawaii for a few years, while I moved on to junior high where I resumed my natural position in the social pecking order, among the solitary geeks for whom the mere prospect of a school dance was a form of cruel and unusual punishment. This was long before geeks acquired the kind of regional chic that provides some social cover in urban areas at least. Back then, there was no technological glamour to protect the socially awkward.

And then, just when it seemed it couldn’t get worse, we moved to a new neighborhood several miles down the highway. The house was bigger. I had my own room for the first time in my life, at age thirteen. For a few months this seemed like it might be the start of something good. But that was before any of us knew that the contagion of recklessness that Uncle Rick had broadcast like a kind of seductive pollen had taken root in my mother, who had made a whole lot of friends in our old neighborhood, including a wild bunch who liked to drink hard and party long. My father hated them all. I think he may have hoped that by moving us a few miles away he could stop their influence over my mother. Of course, at the time, none of us had any idea just how far gone my mother was, and how much farther she would go.