It’s not as easy as it once was to get lost in this world.

In these technology infested times, the proliferation of gadgets that can tell you where you’re going, how to get there, and what it will cost you has taken some of the zest out of travel. Still, most of us would gladly trade the thrill of the unexpected for the assurance that we’ll get where we want to go without undue bother. And after hearing about the recent mid-air mental snaps of some airline staff, I find myself warming to the idea of a quiet book by the fire.

But, like it or not, sooner or later all of us have to get out of the chair and go places, even if it’s only to the dentist. This is why maps will never go out of style.

I love a good map. I can spend hours perusing Rand McNally, marveling at the curious names of tiny hamlets, the abundance of rivers and streams and mountains between the Atlantic and the Pacific, the sheer expanse of our nation.

Yet part of the magic of maps lies in all that you can’t see in them. The personal, political and social history played out in states and cities, to say nothing of the immense physical changes which take place at a pace too slow for our human eyes to fully appreciate. You can get a sense of it at the Grand Canyon, but if we were able to view the rest of the world through that same staggering perspective we might have a better understanding of how long history is, and how short our share of it.

Of course, we’d rather not think about that. We are the center of the universe, after all. The crown of creation, etc. Uneasy lies the head.

But maps – those flat, two-dimensional renderings of the world as we see it – allow us to feel some measure of control. We know where we’re going. We’ve got a map.

Would that it were so easy. The comforting illusion of control that maps provide allows us to function in a world of restless dark matter.

Much as I love maps, I never fully trust them. Everything changes. Roads close, new roads get built, shorelines change, lakes and rivers dry up. The physical landscape has a life of its own, and while our attempts to keep track of it have improved dramatically since the age of satellites and computers, there’s still a gap.

Perhaps that’s one reason why the maps I enjoy most are of imaginary places. As I child I delighted in the map of The Hundred Acre Wood drawn by E.H. Shepard for the Winnie-the-Pooh books. Since then I’ve always had a fondness for a good imaginary map. I love it when a writer takes the time to fully imagine a world, complete with place names that ring true. Most recently the maps in George R.R. Martin’s brilliant A Song of Fire and Ice have been especially satisfying, and very helpful to a reader embarking on the journey through the epic five-volume (and counting) fantasy.

Of course, in order to create a map of an imaginary place, it helps to have a vivid imagination. To believe in such a map can serve as a coping strategy: “when reality fails and negativity don’t pull you through” (thanks be to Bob) you can always retreat to someplace imaginary until the next election.

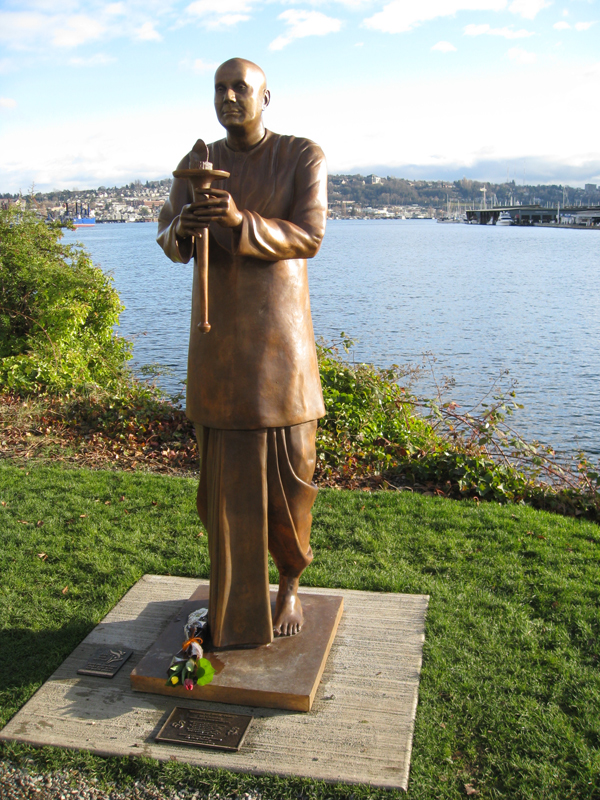

Camped out on the far northwest edge of the nation, Seattle sits on a faultline between the real and the imaginary worlds. It’s easy to cross that line here. That’s one reason I included a map of Seattle in my recent fantasy novel, The Goddess of Green Lake. A map of Seattle is a map of an imaginary place. Here people carve out curious niche lives that couldn’t find a toe hold in Kansas, or in New York City, for that matter.

But here, where the moss grows faster than the national debt, crazy ideas can relax and put down roots. There’s a fair amount of live and let loon attitude. As Mal Reynolds, the noble renegade captain in Joss Whedon’s space-western Serenity once put it: “We’re all out here on the edge. Don’t push me and I won’t pull you.”

While the political stew bubbles and spills with daily infusions of invective and innuendo, it’s helpful to step back, squint your eyes, and try to see the bigger picture. All of this has happened before. Apocalypses come and go. Sooner or later we all dance with the stars.