Summer officially begins June 21st. In other parts of the country shorts and flip-flops will be worn, barbecues will smoke. Some people may even work up a sweat at local ball games and festivities.

Summer officially begins June 21st. In other parts of the country shorts and flip-flops will be worn, barbecues will smoke. Some people may even work up a sweat at local ball games and festivities.

In Seattle, summer arrives like a rock star, fashionably late and so beautiful that all is forgiven. You can’t stay mad at a summer like that. You don’t want to waste a minute in pointless ire.

But all too often it takes an act of will to believe in summer here before July. The weather rarely provides supportive evidence. The forecast for tomorrow is typical: a high of 61 degrees with an 80 percent chance of showers throughout the day. Folks back East might find such a forecast discouraging. In Seattle, it’s parade weather.

And nobody parades quite like they do in Fremont, the neighborhood whose self-proclaimed position as “The Center of the Universe” belies its decidedly leftish bent. Fremont champions the quirky and the freedom to come as you are, or who you wish you were, or whatever. No one will judge you on your attire, or lack of same, and the annual Fremont Fair Solstice Parade kicks off the summer season whether or not summer, as traditionally defined, has arrived.

The parade is famous for its first course: the hundreds of naked bicyclists who streak by the crowds, flaunting feathers, flowers and bodypaint. But the real excitement arrives with the bands. They don’t exactly march. And their costumes lean more toward Mardi Gras than military. Their rhythm is irresistible. Playing everything from hip-hop to salsa to swinging zoot suit tunes that defy categories, these bands rock the streets.

But for my money the unsung heroes of the Fremont parade are the strong silent crews who power the floats. Because, in accordance with Seattle’s ubiquitous “greener-than-thou” ethic, the Fremont parade has one rule: no machines, motors, electricity or animals can be used to move the floats. It’s all old-school push and pull by strong silent men and women. Even in the chilliest weather you can easily pick them out. They’re the ones sweating.

Many visitors to Washington, D.C., never get beyond the nexus of grandeur and gee whiz spectacle concentrated around the Capitol and the National Mall, but for those who venture past the gentrified corridors of power, the city has its share of fascinating sights, though not always an abundance of wealth to maintain them.

Because of its unique status as the last continental colony (taxation without representation remains a fact of life in D.C.) the District of Columbia has long suffered under the benign mismanagement of Congress, which controls the city like a benevolent but harried great uncle who doesn’t really care what happens in the city as long as his chauffeur can always get through the traffic easily and deliver him safely from one seat of power to the next.

Those lacking access to such power can be grateful for the magnificent museums which we are all welcome to visit and support with our tax dollars. The District is forced to operate under the oversight of Congress for funding of its schools, emergency staff, police and parks, to say nothing of roads, water, and the thousand and one little things that go into making a city livable. To its credit, D.C. has managed to survive centuries of neglect, in part because of the energy and resources of some of its residents.

On a recent visit to the “other” Washington I got a chance to spend a little time appreciating the lasting contributions of a pair of remarkable women whose names are less well known than that of Pierre L’Enfant, the French architect whose 1791 plan for the city helped ensure its destiny as a world-class metropolis. A city needs more than grand boulevards and stately monuments if it is to nourish the people who actually live there. Public parks, large and small, are essential. D.C. is blessed by the vision of the Olmsted Brothers, who mapped out the lasting beauty that is Rock Creek Park, a sinuous corridor of greenery and tumbling water flowing from north to south through the center of the city.

But other visionaries have left their marks on the District, with varying degrees of legibility. High up on 16th Street, in an area where few tourists venture, Meridian Hill Park remains a remarkable testament to one woman’s dream of putting Washington, D.C., at the center of the world. Mary Henderson, wife of Missouri Senator John B. Henderson, who introduced the amendment to the Constitution that abolished slavery, settled in Washington in 1887 and began buying up property outside the then-northern boundary of the city. Mrs. Henderson had grand plans for the Meridian Hill area. The place was named for the so-called “Washington Meridian,” the longitudinal line along which nine geographically significant landmarks are located including the Jefferson Memorial, the Washington Monument (give or take a degree), the Meridian Stone on the Ellipse, the center of the White House and the equestrian statue of Andrew Jackson in Lafayette Park.

Mrs. Henderson lobbied Congress for years to support various projects to improve the Meridian Hill area, including one plan to build a bigger presidential mansion on Meridian Hill to replace the White House. Obviously, that bird never flew. But thanks to her tireless efforts the Commission of Fine Arts eventually agreed to develop Meridian Hill as a public park. The result is a remarkable 12-acre European-style strolling garden replete with fountains and sculpture. It was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1974. But even Historic Landmarks need funds for upkeep. On the day I visited, crews were planting new trees on the upper tier. But the equestrian statue of Joan of Arc, a gift to the women of America from the women of France, was still missing her sword, broken off and stolen by vandals some years ago.

On a hillside across town, on a quiet street north of bustling Georgetown, an entirely different sort of garden opens to the public for a few hours each day. Here, beginning in 1921 and continuing for nearly 30 years, the brilliant landscape designer Beatrix Farrand created a work of living art on land owned by Mildred and Robert Woods Bliss. The gardens here are sequestered, carefully maintained and designed with a view to intimacy and introspection.A small admission fee charged during the blooming seasons helps pay for the small army of groundskeepers and staff who keep the gardens immaculate.

On a hillside across town, on a quiet street north of bustling Georgetown, an entirely different sort of garden opens to the public for a few hours each day. Here, beginning in 1921 and continuing for nearly 30 years, the brilliant landscape designer Beatrix Farrand created a work of living art on land owned by Mildred and Robert Woods Bliss. The gardens here are sequestered, carefully maintained and designed with a view to intimacy and introspection.A small admission fee charged during the blooming seasons helps pay for the small army of groundskeepers and staff who keep the gardens immaculate.

The difference between a privately endowed garden and a public park overseen by Congress can be summed up by a tranquil bench in Dumbarton Oaks inscribed with the Bliss family motto: Quod Severis Metes: As you sow, so shall you reap.

Congress might consider adopting that one.

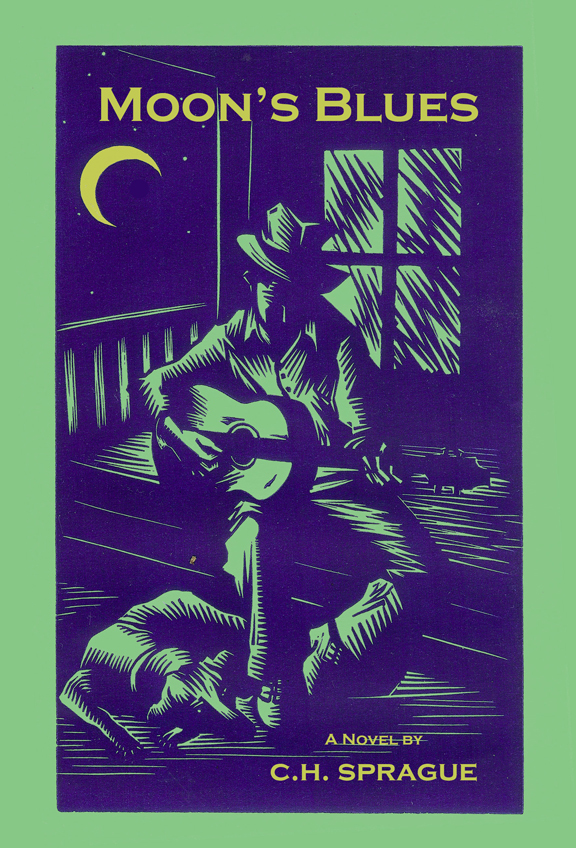

My new book, Moon’s Blues, just went live.

It’s another adventure in the off-the-beaten-path life of Duggie Moon, Latin scholar and slacker extraordinaire. This time out Duggie tries to mend a broken heart in the time honored way, with music, which, as we’ve all been led to believe, can feed the soul, soothe the savage breast, and lull the unwitting into making unwise choices.

At any rate, there’s no question that mountain acoustics lend power to the smallest voice. Ask any yodeler. In the hills and hollows of Rapidan County, Virginia, where the blues and bluegrass weave patterns in the dusky air, homemade music pays tribute to the loved and lost. While many mountain musicians are content to play for family and friends, there are always a few restless visionary types who aspire to stages greater than the front porch. And when these ambitious souls connect, they sometimes play with enough thrust to escape the dense gravitational pull of the mountains and enter into the rarified atmosphere of the big city, where phoenix bands rise and soar before burning up in the intense heat of public expectation.

The dream of riding on the wings of such a band smolders in the heart of many a young man, who may not himself be equal to the task of playing a three chord progression in time, but who knows what he likes when he hears it. Duggie Moon is such a man. And when Duggie decides to manage a motley crew of musical misfits, he’s convinced it won’t be hard to lead them to financial success and popular acclaim.

Even after he discovers that the members of Identity Crisis are one frayed nerve away from implosion, Duggie remains hopeful, knowing that on a good night the band can lift a room to the stars. What he doesn’t know is that lasting success in the music business only comes along once in a blue moon.

Moon’s Blues is available now from Amazon.com and Barnes & Noble.

A garden is performance art of the most ephemeral and transcendent kind.

Blooms come and go. The aspect of the landscape alters with every passing cloud, every sudden shower. So for the travelers like me who go out of their way to visit gardens, it’s always hit or miss. You never know if the garden will be at its best on the one day you have an hour to spare to see it.

But in the stunning Central Garden at the Getty Center in Los Angeles I suspect you could never be disappointed, no matter when you visit. I got the chance to see it last week, and it took my breath away. The museum itself is a glorious structure, designed by noted architect Richard Meier, and sited on a spectacular bluff high above the city, with changing exhibitions of world class art inside. Van Gogh’s celebrated iris painting was among the treasures on display when we were there. But for me, Van Gogh’s irises, lovely as they are, couldn’t compete with the sun-drenched spectacle of the Central Garden.

Designed by artist Robert Irwin in a flowing spiral of stonework which allows visitors to savor the garden’s tapestry of color and texture from constantly changing perspectives, the garden is an oasis of serenity and beauty high above the clamorous city.

Irwin is quoted in the Getty’s brochure saying that his aim was to produce “a sculpture in the form of a garden aspiring to be art.” That he succeeded is obvious.

What is not so obvious is the wondrous fact that the Center is open to the public free of charge. School children by the dozens scamper past the fountains, pose for photos on the parapets. Sure, you have to pay to park at the bottom of the hill before riding the tram up to the Center. And yes, bottled water from any of the kiosks will set you back three bucks. But it would be churlish to complain. To be allowed to walk in flower-scented beauty, warmed by walls of sun-baked stone, to hear the music of fountains and feel the soft breeze on your face, surely this is what paradise should be.

Hope is the thing with petals.

Some welcome spring with flowers. Some with horse races. In Seattle spring means the opening of boat season.

Sure, the boats are here all year round. But on the first Saturday in May the University of Washington’s stellar crew teams compete in annual races which draw thousands to line the banks of the Montlake Cut and cheer them on. In its 108 year history the UW crew teams have won 24 national championships, but winning the local Windermere Cup remains a point of pride for the Huskies. The rest of us can only marvel at their dedication and precision.

On the last day of April a low bank of clouds finally loosened its grip over the city. Then today, Sunday, May Day, the sun shot into a clear blue sky and the constant buzz of lawnmowers carried on the soft breeze.

On the last day of April a low bank of clouds finally loosened its grip over the city. Then today, Sunday, May Day, the sun shot into a clear blue sky and the constant buzz of lawnmowers carried on the soft breeze.

Some feel compelled to weed, dig, clean, whatever. Not me. I’m basking. The clouds, we’re told, will be back tomorrow. Seize the day.

Some like them ripe. Some like them green. Some like them slathered with peanut butter and fried. But most everyone likes bananas.

Now imagine a time when you can’t get them in the store anymore.

That’s where we’re headed, according to an alarming story I read not long ago in The New Yorker detailing the devastating blight which has been wiping out banana plants in Asia and Australia. In the U.S. most of our bananas come from Latin America, so we haven’t felt the impact of the blight yet. But the spread of plant viruses and pests is like the drifting of nuclear dust, only made more visible and with quicker results.

And the reason this blight looms as a greater threat than most is that, although there are more than a thousand different kinds of bananas in the world, the commercial banana industry is dominated by one variety: the Cavendish. That’s the one we slice into our cereal, tuck into our lunch bags, mash up for banana bread.

Once the Cavendish is gone, no doubt commercial growers will switch to some other variety and future generations will grow up never knowing what “real” bananas tasted like. And life will go on, as it tends to do, evolving, shifting, vanished species making room for upstart newbies. Sometimes I wonder what will take the place of humans once we’ve finished wiping each other out.

Of course, I’d like to think it’s still possible that we may learn something from all those bananas. The other thousand varieties of bananas which are resistant to the blight may not taste the same as Cavendish, or look the same – some of them have red or brown skins, for instance – but they have unique flavors and nutritional values which could spice up any meal. For this diversity we should be grateful.

As Michael Pollan pointed out in his brilliant and sobering book The Omnivore’s Dilemma, one of the most insidious problems in the modern food industry is the constriction of the food chain to a few links. The corporate empire built upon chemically dependent genetically engineered corn and soy production encourages a synthetic diet as empty of true nourishment as the vapid marketing slogans used to sell it. “Coke Is It”? Really? I think not.

The word diversity has been bandied about so much in the last couple of decades that people tend to stop listening when they hear it. The word has become a kind of shorthand for everything from fairness in the workplace to enrichment of our culture. But in terms of our planet, diversity is Nature’s insurance policy. It’s a failsafe system so that if we lose one butterfly to a menacing microbe we don’t lose them all. If we lose one elm to a bug infestation, we can still find shade under other trees.

The same principle applies with our own species. We need each other, all the shades of humanity, to ensure our strength and our future. Sure, we all have our differences. We argue, we fight. We kiss and make up. That’s what families do. It sure beats going bananas.

It’s that time when the baseball season has begun, and the first losing streak (seven games) has been snapped, and the diehard fans are still clutching those season tickets with a kind of wistful, albeit delusional, hope that this will be the year the Mariners prove they’ve got what it takes.

It’s that time when the baseball season has begun, and the first losing streak (seven games) has been snapped, and the diehard fans are still clutching those season tickets with a kind of wistful, albeit delusional, hope that this will be the year the Mariners prove they’ve got what it takes.

Not that anyone really believes this. But it’s the hope that carries us along, as we watch King Felix pitch with consistent conviction only to be undone by the limp bats of the offense. No offense. But really, that’s the problem. Again. At times last year it almost seemed as if the announcers could have phoned in the analysis.

But that’s baseball. Some teams got it. Others . . . not so much.

Still, if you get hooked on the dance to the music of baseball, you have to be there. Good or bad, win or lose, the game remains strangely hypnotic for those of us who give in to it. Since moving to Seattle I have learned to love baseball in a way I never did before. After years of watching soccer and tennis and even football, the game of baseball offers an entirely different kind of narrative. I’m continually intrigued by the variety of skills, and strategies, and personalities, by the slow unfolding of each game’s drama.

And at the heart of the game is the dynamic fulcrum of risk – the cagey battle between pitcher and batter. To swing or not to swing. It would seem a simple question. But when every pitch varies in speed and trajectory, it’s not so simple. And what can be more annoying than watching a perfect strike go by without taking a swing? I imagine it’s hard to judge a ball whizzing past at 97 mph, as they often do in Major League Baseball, so I have a lot of sympathy those guys.

As a writer, I’ve had some experience with pitches. Not the kind you see in the ballpark, but the kind that editors and agents demand before they’ll consider reading your work. A good pitch can open doors in the publishing business. But these days, the sheer volume of pitches being thrown in the publishing industry is so overwhelming that few editors and agents will consent to swing at anything unless the writer has already done some heavy lifting.

At the last writers conference I attended the most popular buzzword in the seminar programs was platform. As in: you have to have a platform if you want to be a successful writer. It’s not enough, apparently, simply to write whatever it is you feel driven to write. You have to build a platform – blog, Tweet, tour, plaster your name in as many places as possible to create buzz about yourself, to reach your target audience, to keep them informed about your books, your life, and enable fans to connect with you.

All of this sounds reasonable, I suppose. But the reality is, if you really want to build a platform, it takes money, time and a lot of effort which might otherwise be put into your writing.

So, as I’m gearing up for the publication of another book, coming soon to a web site near your computer, I’m thinking of pitches and platforms, promotions and pop flies. I’d like to think that I have fewer illusions about my writing career than I do about the Mariners’ chances of making the playoffs.

But, truth be told, I’d love to hit one out of the park.

Will it be “Moon’s Blues,” my up and coming light novel about an affable geek who tries to impress his girlfriend by managing a rock band? Probably not. But you never know. It’s a long season. Anything can happen. That’s my platform.

I went back home last weekend.

Home. That place where, famously, if you go there, they have to take you in.

There are still a lot of familiar faces in the area where I spent most of my early life. And a lot of the familiar landmarks remain recognizable. East is still East. West is still West. But the direction home is no longer obvious.

The house where my family once lived together has been sold. The family itself was fractured long before. Friends have moved away. Businesses disappear. Trees age and die. The landscape alters.

I realize this is simply Time working its inexorable magic. Everything is mutable. But the human heart longs for something permanent. Thus our popular music overflows with clichés about home, “where the heart is,” “where my thoughts are straying,” etc., etc. Home, where, as George Carlin once pointed out in his brilliant monologue about the difference between baseball and football, you are safe.

Maybe that’s only in baseball. In real life, home isn’t reliably safe. Bad things can happen at home. Tragedy, heartbreak, cruelty and despair can suck the life out of any home. Yet, much as the longing for adventure and excitement lures us to seek out new places, the magnetic True North of Home grounds us to an emotional core. It’s the primal hug that makes sense of all human experience.

When I went “home” last weekend it was a bit unsettling to drive through the old familiar terrain and feel like a tourist. The actual reunion event was taking place in Delaware, a state in which I’ve never lived, though I have many fond memories of summers at the beaches there. And this event had the feel of another vacation, albeit truncated by the frantic pace of modern life.

Still, once I got there, and was surrounded by family members, some of whom I hadn’t seen in decades, the setting didn’t matter. The connection was immediate and profound. Time slipped a gear as the links of memory connected, the chain of shared experiences burnished to a new luster, bright as the silver on Patty’s necklace, lilting as Leslie’s laughter.

This is what home is to me now. Not a place on Earth, but a place in mind.

The hardest thing about growing old is the realization that it’s all going by so fast, and you really can’t take it with you. But as long as there are family and friends who share your sense of what makes life worth living, it doesn’t matter where you are. As The New Yorker writer Joan Acocella once put it: “Some people guard their home territory. For others, home is something inside them, and they can take it with them.”

That’s my new plan. With my home inside me, I’m home wherever I am.